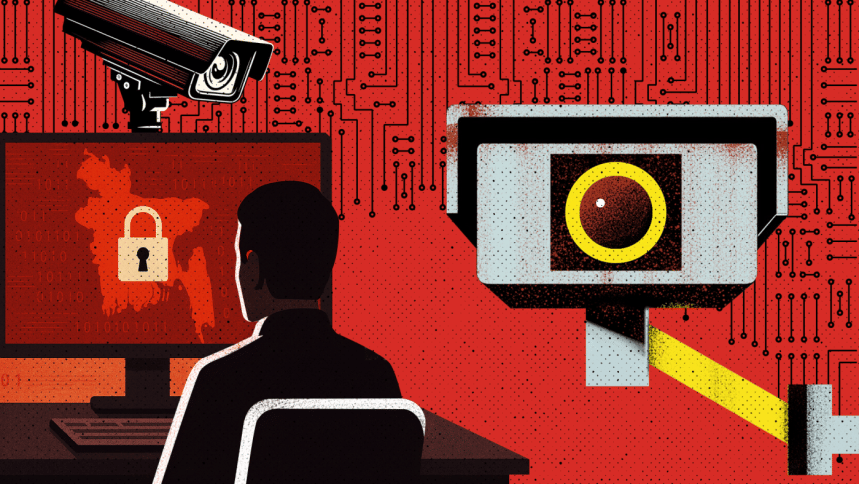

Bangladesh, much like other contemporary nations, possesses a well-established system of surveillance. This infrastructure did not materialize suddenly; rather, it evolved over time in response to various crises. From political assassinations in the 1970s and 1980s to attempts on the lives of foreign officials, and from mutinies within paramilitary forces to terrorist incidents over the past few decades—each national tragedy has served as a pretext for the government to enhance its control over the populace. With each occurrence, the surveillance mechanism grew more robust and less accountable. What initially began as a reaction to security challenges has transformed into a tool for consolidating and maintaining political power.

Since the early 2000s, consecutive administrations in Bangladesh have systematically reshaped the country’s legal and regulatory framework to normalize extensive surveillance practices. Under the reign of the Awami League for over 15 years, this system has facilitated the routine suppression of dissent, arbitrary detentions, forced disappearances, and extrajudicial killings. However, this shift did not happen in isolation; all branches of the government have played a role in legitimizing a surveillance regime that undermines the very values it purports to safeguard, whether through active enforcement, tacit approval, or institutional neglect.

The surveillance capability of Bangladesh does not commence with the installation of cameras; it starts with budget allocations. In the fiscal year 2023-24, an amount exceeding Tk 63,000 crore (around $5 billion) was earmarked for the Ministry of Defence, the Armed Forces Division, and the Public Security Division—the foundational components of the nation’s civilian and military intelligence structure. This budget forms the backbone of Bangladesh’s surveillance infrastructure; however, the specific funds allocated for technologies that track, profile, or monitor individuals remain undisclosed. There is a lack of parliamentary oversight and statutory safeguards to ensure that procurement decisions align with the Constitution of Bangladesh and international human rights standards.

An investigation by Tech Global Institute revealed that between 2016 and 2024, law enforcement and intelligence agencies in Bangladesh acquired over 200 surveillance devices and software systems, although the actual number could be higher due to the lack of transparency surrounding these transactions. These acquisitions include IMSI catchers, GPS trackers, drone systems, facial recognition technologies, and communication intercept tools—obtained without substantial public consultation, export-import controls, or legal protections.

While existing laws such as the Public Procurement Act, 2006, the Public Procurement Rules, 2008, and the Import Policy Order establish guidelines for transparency, competition, and import regulation, they notably overlook human rights considerations. There is no legal mandate for authorities to conduct due diligence or audits to ensure that imports capable of tracking, profiling, or monitoring individuals comply with domestic or international human rights norms. Moreover, procurement decisions made in “good faith” are shielded by legal immunities, shielding officials from challenges even when rights are violated. In the absence of robust accountability mechanisms, state actors face minimal resistance to overreach and are sometimes incentivized to pursue it. Consequently, the laws are structured to perpetuate systemic impunity, shielding officials from legal repercussions while leaving citizens with limited avenues for recourse.

The current legal and regulatory framework governing surveillance in Bangladesh consists of a disjointed assortment of laws that grant broad, largely unchecked powers to state entities. Research by Tech Global Institute identified over 20 different laws that authorize surveillance, often using terms like “monitoring” and “interception” without clear legal boundaries, allowing for arbitrary surveillance under the broad justifications of public safety and national security.

At the core of this framework are longstanding statutes such as the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulation Act, 2001, and the Telegraph Act, 1885, which empower the executive branch to monitor, intercept, record, and collect extensive user data across the telecommunications spectrum—from international gateways to mobile network operators and internet service providers. These provisions are not accidental but are rooted in colonial-era laws designed for dominion rather than democratic governance. Their continued enforcement in the modern era reflects a conscious decision in statecraft, perpetuating a legal framework that views citizens not as rights holders but as subjects to be surveilled, managed, and marginalized.

Supplementing these statutes are licensing conditions imposed by the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC) that effectively institutionalize surveillance as a mandatory aspect of operating in the telecommunications sector. For instance, Clause 25 of the 4G license agreement mandates mobile network operators to facilitate real-time access to user data, bulk data interception, and live database monitoring by security agencies like the National Telecom Monitoring Center (NTMC). Operators are also required to identify and report users flagged as national security risks. While the specifics of compliance are opaque, these obligations likely occur without meaningful user consent or knowledge. Compliance is enforced not only through the threat of legal action and financial penalties but also through coercive administrative measures such as non-renewal of licenses or permit withholding, making resistance financially unviable. Nevertheless